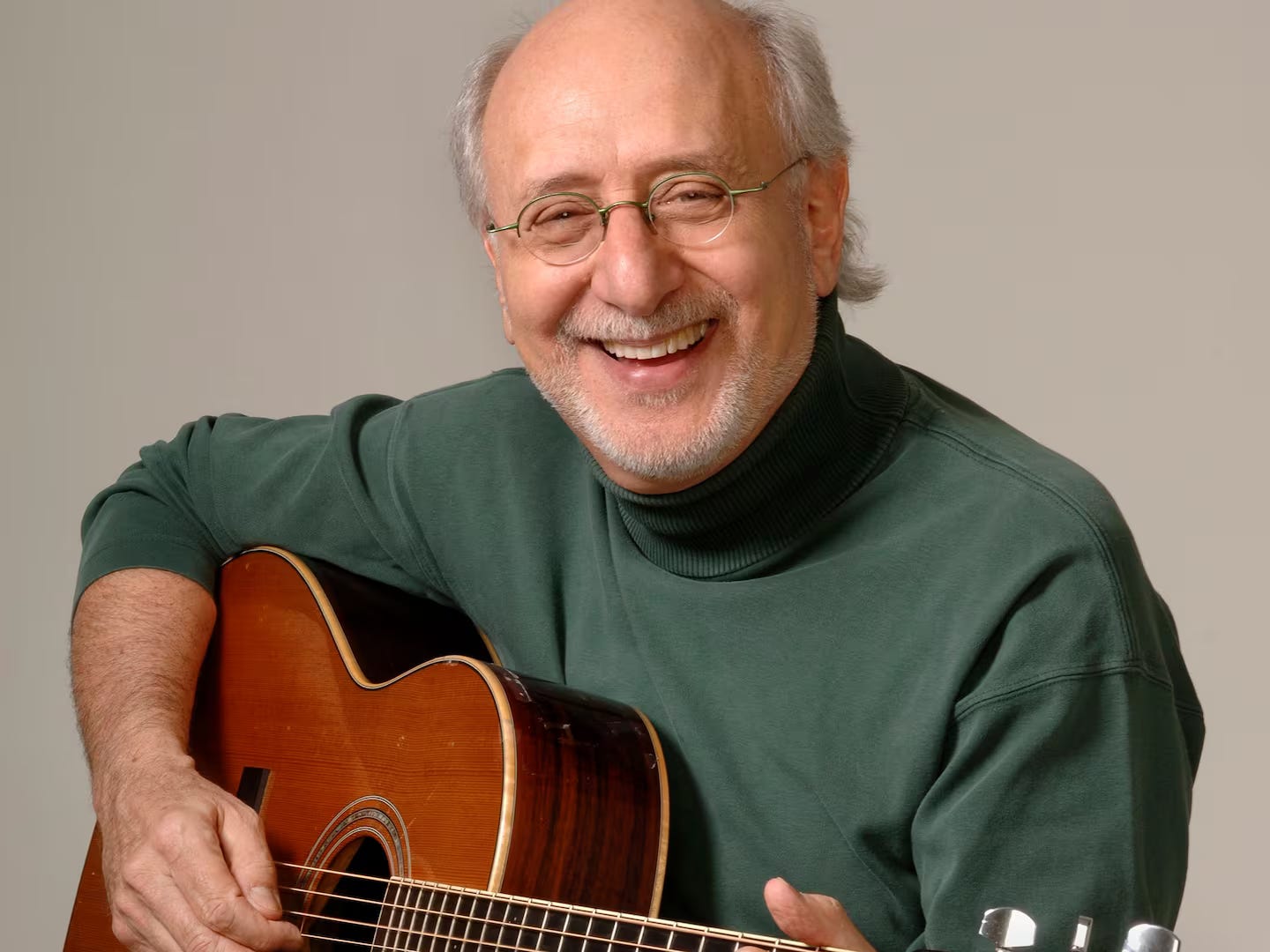

Peter Yarrow: Extending Folk's Traditions

"This was a path forged by Pete Seeger," says Peter, Paul & Mary's tenor (1938-2025)

Peter Yarrow, the empathetic tenor of the 1960s folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary, died Tuesday at 86 in New York, after a long career of performance and activism with the trio that helped widely popularize the folk movement at the dawn of the 1960s.

It was Yarrow’s voice on his first hit with Mary Travers and Noel Paul Stookey, with whom he had been combined by manager Albert Grossman before he began to manage Bob Dylan.

“Lemon Tree” was a lilting song by Bob Holt borrowed from a Brazilian tune in the 1930s. Their second hit, the emphatic “If I Had a Hammer,” originated from Pete Seeger’s group The Weavers, the earlier harmony folk act on which the trio was modeled — except as a hipper, cooler version.

Even so, they were part of a continuum.

“There was a thread in music that made people think they were part of a real positive shift in the world and in their country, and their participation would make a difference,” Yarrow told me in 2014. “This was a path that was forged by Pete Seeger, who made every appearance he made resonate with the conjunction of music and his dreams and hopes for a world that was just and fair and humane and equitable, and in the last years, that would survive.”

A younger world is getting re-acquainted with Seeger through his representation in the Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown. Yarrow’s figure pops up in it too, as the one who introduces Dylan’s fateful electric set at the Newport Folk Festival.

While Peter, Paul & Mary’s debut album, with its two hit singles, sold more than 2 million copies and stayed in the Top 10 for 10 months — and in the Top 20 for two years — they had an even more significant hit singing Dylan’s “Blown’ in the Wind.”

Somewhat ignored when released three weeks earlier on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, his second album, the Peter Paul and Mary version went to No. 2, sold a boatload and won two Grammys. In addition to helping gain Dylan wide attention, it became an enduring anthem in social activism after the trio performed it at Martin Luther King’s 1963 March on Washington — one of the groups many of their performances at key historic moments, from JFK’s inauguration to any number of protest rallies over the decades.

I first talked to Yarrow in 1993 about a family concert by Peter Paul and Mary that was giving Barney the Dinosaur a run for his money on public television. It was more than just playing his “Puff the Magic Dragon” alongside classics like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “If I Had a Hammer,” he said. “It’s the handing down of a legacy we ourselves have received and shows the way in which folk music allows evolution of a sense of community in a microcosm.”

The success of Peter, Paul and Mommy, Too, at the time “has been acknowledged as a renaissance of Peter, Paul and Mary,” Yarrow said. “It’s the touchstone of us being together. And it has many ramifications: personal, historical and musical.”

And it had a similar effect, seen in the eyes of the young and old who surrounded them in that show, taped in Brooklyn.

“You sit there as a member of the audience, not as some group-think phenomenon, but as individuals who have created a closeness, a mutuality, a sense of concern and caring, and ultimately a feeling of empowerment, which folk music has always generated.”

It was that sense of community that drew him into the folk world back at college in Cornell. It was enough to lure him to New York City in the height of the GreenwichVillage folk boom of the early 60s. And it was something he helped in engender in new generations.

“Today, we see the re-emergence not only of folk music, ‘unplugged’ or acoustic music, but a crying need for a language which somehow says, in spite of all the failures of our society over the past number of years, to respect the values of each person and nurture him or her and proclaim there are no discards, that we need everyone,” Yarrow said.

At the time of the interview, Yarrow was frankly annoyed that I hadn’t actually seen Peter, Paul and Mommy, Too before our chat.

“What if I had been a part of creating ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ and you hadn’t seen it?” he asked.

If the concert special wasn’t exactly Shakespeare, a lot of work went into each song, he said after he called back for a follow-up — after I had viewed the video.

“We don’t have great voices,” Yarrow said. Rather, “We have voices that portray what we feel inside. That’s the kind of quality I hear in music, from Mississippi John Hurt to Bonnie Raitt.”

Artists like Hurt, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Josh White and Lead Belly helped influence the trio, as well as “all those singers of union songs who struggled to give the rank and file a voice”

Many of the songs were repressed in an era of anti-Communist crackdown — “a very dark time in our history,” he said. “It’s taken 40 years to reconstruct the idea that an expression of communal responsibility is not a Red threat.”

At the family singalongs, as parents learned the suppressed verse of “This Land is Your Land” that was denied them in school, their kids were learning and singing “We Shall Overcome.“

“These songs are not just songs,” Yarrow declared. “When we sing them together, all of a sudden there is a cumulative effect. When we sing them, we’re singing our history. They have great meaning. They’re incantations of our shared history.”

When I talked to Yarrow in 2014, it was for a story I was doing for The Washington Post about a book marking the trio’s 50th anniversary, Mary by then was gone, having died in 2009 at 72. But they used her voice, adopted from her own autobiography and speeches she had made on stage, incorporated into her into their narrative — speaking in one voice.

“It’s a celebration of 50 years together,” Yarrow said at the time — though they had actually been formed more like 53 years earlier. (“It took a couple of years to get it together,” he said.)

One detail that emerged from the lavishly illustrated book was their tradition of running onto stage, hand in hand, for each performance instead of simply walking on.

“I guess it started with a sense of joyfulness, rather than … dignity,” Yarrow said. “It was natural. It was never a discussion, never something that we were told to do. Except at the end, when Mary was in a wheelchair and with an oxygen tube. We didn’t run with the wheelchair. But she insisted on performing in those last months, when she was wheelchair bound. She wanted to do it.”

After Mary died, the remaining two continued to perform and were still in demand at activist events. “Noel and I sang together with the parents of Trayvon Martin and the father of one of the children that had been killed in Newtown,” Yarrow said. “So it’s not just the spirit of the work continuing but literally the work itself.”

But even when the two men sang together, Mary was with them too.

“When you hear us sing together,” Yarrow said, “you will hear the spirit of Mary in our voices. It’s there! We sang together for almost 50 years. So we’re carrying it on not just in terms of the intention, but we’re carrying it on, quite literally, with that energy and that history and that lingo, that shared syntax, that way of thinking.”

Presumably it’s up to Stookey, who just turned 87 — or a new generation of folkies and activists — to carry it forward now.