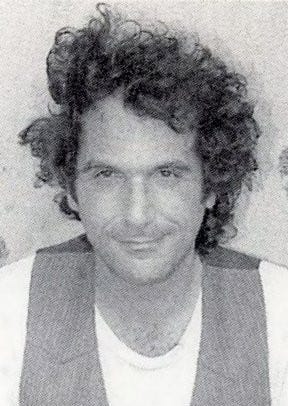

Remembering Charlie Burton, 1950-2024

An all-time favorite rocker-songwriter and renegade, who deserved wider reknown

It was very hard to hear, though the salutes on social media, the death at 73 of the pre-eminent Nebraska rocker and forever unsung artist, Charlie Burton, the frenetic, funny and singular barroom performer of whom I’ve been a fan nearly half a century.

His death Sunday, a week before his 74th birthday, was confirmed by Burton’s son and daughter to Lincoln writer and filmmaker Jim Fields, who had posted it to a Facebook site dedicated to Charlie (that he would have nothing to do with).

I first saw Charlie as part of the Solid Senders, which quickly became Rock Therapy in 1976 and then a half dozen clever names through the years in hundreds of gigs and a handful of recordings— the Cut-Outs, the Go-Cups, the Hiccups, and then, years later, the Texas 12-Steppers, the Dorothy Lynch Mob.

I merged my fandom and journalism into a bunch of articles about him in every paper I wrote for — the University of Nebraska-Omaha Gateway, the Council Bluffs Nonpareil, the Omaha World-Herald and even after I moved to Connecticut, the Hartford Courant.

Turns out there wasn’t just a local connection then, but I was still trying to convince people, just as I had done for friends for decades, of his greatness. So I’ll leave you that piece I did in 1995 after a trip seeing him at South by Southwest as a way to explain.

I’m traveling now, but when I get back I’ll dig out other artifacts and arrange a proper salute here and on the Capital Radio show I do at cygnusradio.com.

Xxxx

It was one of the foremost music conventions in the country. Thousands of industry bigwigs were flying in to Austin, Texas, to discover new bands or hear such current buzz-makers as Elastica, Sublime or Ned’s Atomic Dustbin.

The many choices of performers made it tough to decide whom to see at the annual four -day South by Southwest Music + Media Conference. The number of bands seemed especially plentiful on that Saturday.

Bt there was no question where I’d be going that night — to an off-the-beaten-track, non-conference-participating coffeehouse, on whose chilly deck would be one of my favorite performers of all time, Charlie Burton.

All weekend I had been acting like something of a shill for Burton’s gig, jotting down details for those I thought would be interested — the writer from Charlie’s hometown paper in Nebraska, the reviews editor from Rolling Stone.

The latter was familiar with Burton; he’d singled him out in a 1991 piece on the Austin conference, labeling him “rough-riding Fifties psycho-billy, punched up with manic corn.” It was, in part, because of that reception — and a quick-blooming but ill-fated romance — that Burton cut ties with his longtime band to move to Austin.

For years Burton had been king of the music scene in Nebraska, though lately he’d been respected more as an elder rock figure — if he was respected at all. The scattered, indifferent applause on the strange 1991 live album “Puke Point at the Juke Joint” showed his career had gone full circle.

When I began following Burton nearly 20 years ago in the mid-70s, with a band called Rock Therapy, the crowds gave the same puzzled, pitiful response. Here was a strange band playing a kind of music nobody had ever heard before —a super-charged brand of rockabilly that the group had made his own.

The energy of the music predated punk, but the songwriting traditions grew out of the droll wordplay of the Kinks’ Ray Davies. And burton’s stage manner — his comic introductory patter and his ever-changing approach to songs — made it worthwhile to see him every night of a weekend run in Omaha.

When then, Mr. Rock Critic, doesn’t anybody know the name of Charlie Burton? That is a question that continues to linger.

Charlie Burton was raised on classical music. After moving to Lincoln, Neb., his father, who hailed from Hartford (his mother was from Wallingford), brought classical music to the prairie with the first FM commercial classical station between Chicago and San Francisco.

“In our house,” FM meant Fine Music, and AM meant Awful Music,” he once told me in an interview.

But Burton sneaked many a listen to that demon rock ’n’ roll on a transistor radio he had won from a local TV repair store. And it was that Awful Music, in its early ‘60s exuberance, that inspired him.

While attending the University of Michigan, where he saw supercharged groups like the Stooges and MC5, Burton began writing for Rolling Stone. He became the young magazine’s country music columnist but was also tapped to write major reviews on everyone from Iggy Pop to Ringo Starr. When rock critic Jon Landau wrote in a famous essay that critics couldn’t cut it as performers, Burton felt challenged. He put the pen down to prove Landau wrong.

Returning to Nebraska at age 21 to take over the family harpsichord-kit business from his ailing dad, Burton led a success of vibrant bands, including Rock Therapy, the Cut-Outs and the Hiccups.

His first single, “Rock & Roll Behavior,” released the day after Elvis Presley died in 1977, was voted No. 2 in the annual Village Voice critics’ poll.

Burton quickly became legendary in Nebraska, but he also drew notice in Minneapolis and Dallas. The band made occasional pilgrimages to New York in rickety vans, including one snowy night in 1978 when they went to the famous punk dive CBGB’s, where Johnny Rotten went to see them the night after his Sex Pistols broke up.

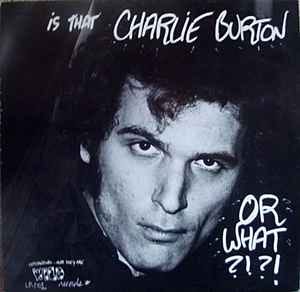

Burton’s first album didn’t come until 1982, with “Is That Charlie Burton … Or What?!?!, followed by “Don’t Fight the Band That Needs You!!!” (1083) and “I Heard That” (1985). His first CD, “Green Cheese” (1990), finally married his classical and rock sensibilities in the speeded-up rocker “(You’re Not Playing Fair) Elise,” for which Burton shares songwriting credits with Beethoven.

Burton and his band were continually touted by such arbiters of musical taste as the New York Rocker, Musician Magazine and Trouser Press, whose lingering editions of its record guide call his music “wonderfully unpretentious, hopped-up / stripped down rockabilly/R&B originals with offbeat, often funny lyrics. Nothing fancy or remotely contemporary — just gutsy and great!”

Burton also had his supporters in the music world. The 1983 “R.E.M.: The Rolling Stone Files” (Hyperion) reprints a 1983 article in which R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck mentions Burton and the Cut-Outs in the same breath as the Replacements and Hũsker Dũ as one of the country’s top regional groups.

While the music world went through disco and punk and post-punk and metal phases, there seemed little place for Burton’s homegrown fun. His song “can’t Find My Niche” seemed prophetic.

Still, he plugged along, on gigs big and small, allowing him to lay claim, on one bio, to being “the only entertainer to have shared stages with both R.E.M. and REO” Speedwagon.

His failure to catch on nationally was a boon to local fans, who could continue to see his act as often as possible. I regularly cited Charlie Burton as one of the great benefits of living in Nebraska. Of course, my family lived there, too).

When I moved East, I tried to convert my friends. I’d bring them cut-out copies of Cut-Outs albums. I’d gather drops to see him at tiny gigs in New London or New Haven. In one such show at the Grotto, a college-age fan gave Burton a paperback book with the same name as one of his songs, “Succubus.” If someone this far from the heartland can be so touched, I thought, maybe Burton had a chance.

But he didn’t. In a world that didn’t stop spinning out new bands and gobbling new trends, attention naturally turned to the younger ones.

Burton’s 1992 move to Austin was a jolting shakeup: No longer a local hero, he had to fend for himself in a town overflowing with musicians.

With unexpected profits from the sale of his Lincoln home, he got to pay top-notch talent to play on a new single, “Spare Me the Details,” a takeoff on the style of Johnny Bush, a country music contemporary of Ray Price. Among the assembled were Mark Rubin of the Bad livers, Mark Korpi of the Naughty Ones and John Ely, formerly of Asleep at the Wheel, on pedal steel guitar.

The single’s flip side, “(It Must Have Been) Someone I Loved” was a throbbing ballad, expertly done, with a vocal prowess Burton had rarely shown on record.

But commercially speaking, the single was doomed. Today’s country radio hates old-sounding twang, and modern rockers don’t like country at all. Burton’s 500 copies “on yummy blue vinyl” are destined to languish despite the funny details: the band’s name is the Texas 12-Steppers, the label is Loss Lieder, and the cover is a direct copy of a Johnny Bush LP, lifting one of his record’s testimonials.

While Burton could score top musicians for the session, it was tougher to line up regular musicians for a gig. And so the revered rock figure paid the rent by clerking at music stores, not making enough over expenses to even mail out singles to rock writers who had responded to him in the past.

But by the time the South by Southwest conference rolled around in the spring, when Burton was sure his bass-playing pal C. Buggs Coombs would be coming down from Michigan, he organized a group that included ex-Junior Brown drummer Steve Wheelis and young Berklee guiitar whiz Joel Hamilton.

Not even bothering to apply for an official gig, Burton landed the coffeeshop show. The guy from Rolling Stone didn’t show up. Neither did the guys with Lincoln ties. Nobody expected Matthew Sweet to show up — and he didn’t — but why not? Sweet, who had headlined a huge outdoor show the day before, grew up in Lincoln and like a lot of young rockers there, credited Burton as a mentor.

Despite the crowd size Burton played his heart out and won over the coffee drinkers on hand.

The sound that night was necessarily subdued — a single snare drum and turned-down instruments — and seemed to turn more to country than rock. But it had everything, from the great single “Guitar Case,” to newer tunes like “Out of My Hair, Not Out of My Mind” and an irresistible twist on an old Elvis Presley title that he called “Come Back Baby, I Wanna Play God with You.”

The standout that chilly night was an introspective tune called “Embarrassment of Riches,” which, like an earlier tune, “One Man’s Trash (Is Another Man’s Treasure),” has too many specific details to be wholly fictional:

I know that the details of my life are awfully boring

But it’s the stuff I think on as I lay my vinyl flooring

Tho’ many of my high school friends have gone on to comfy niches.

Looking back, I’d say I’ve had an embarrassment of riches.

The next night at the conference was about the Guided by Voices show. Here was, supposedly, the breakthrough gig from the rock band from Dayton, Ohio, that had been playing and recording in obscurity for more than a decade.

The band’s leader, Robert Pollard, a former teacher well into his 30s, is one of a few folks plucked from obscurity for songs they’ve been doing for a long time. Jack Logan, 35, a small-motors repairman from Georgia, had 42 of his track relay at once on the album “Bulk.” And the career of Joe Grushecky of Pittsburgh, onetime leader of the Iron City Houserockers, was revived when Bruce Springsteen agreed to produce his new project.

So if each of these rockers can be discovered suddenly, deep into their careers, why not Charlie Burton at 44? Why not now?

Xxx

It didn’t happen. And maybe, looking back, I always paid too much attention to music world success over the great art he was creating in the moment. The apex was the live performances. The records were very good, but didn’t quite reach those heights. The video performances seem sanded-down for wider audiences. Relishing those ever-changing gigs was the best part.

I’d track Charlie’s performances when I’d return to Nebraska annually to see family. Once I planned a trip around one of his scheduled Friday afternoon gigs at the Zoo Bar in Lincoln — only to find that it had been pre-empted by other Cinco de Mayo plans.

A video of a house performance of some new and old songs during Covid was strong enough to get me through the pandemic. But those songs never quite got released.

I guess I’ll continue my quixotic quest to spread the word of his greatness when I get back home. An embarrassment of riches indeed.

Used to tend bar at the Zoo early 80's. So saw him alot. But when i was not and out with friends, we often sat near the front. And, i kid you not, Nancy, a friend of ours, would get a pitch of beer spilled on her every time. We always thought Charlie had picked her out, somehow. Long live 'Breathe for me Presley' and 'Met my baby at a garage sale'. RIP

Roger,

I wanted to touch base. I saw your column on Charlie Burton. As a member of the Modern Day Scenics, I believe I did my first show with Charlie at the Lift Ticket lounge in 1979. We went on to do several shows with them at Saner's Lounge and the Howard Street Tavern.

When I left the music business to focus on my career, I lost touch with Charlie. But in 2017, we opened a pub / live music venue (Growler USA initially and then renamed to Mars Bar and Grill after we broke away from corporate).

The first time we had Charlie perform in 2017, he was in the middle of the song Rogue Cop when one of our servers said there was someone at a table that wanted to speak with me. I went over and the man immediately launched into a tirade about the song (he was a cop) and suggested he would never be back and would tell everyone he knew to not visit our establishment. I tried to make the free speech argument but they just walked out.

A few Charlie shows later at our place, he and I sat down to catch up a bit and I relayed the story about the cop to him. He was mortified. He apologized up and down and felt bad for hurting our business.

So that night when they played Rogue Cop, he introduced the song by saying that it was just ONE cop, not all cops and that he had many friends that were cops.

We closed down just before Covid closed businesses in Omaha. There is no way we would've survived that anyway. We bled out a bunch fighting corporate when we broke away from the franchise. We won, but were pretty much out of funds ad that point.

You mentioned in your piece that Charlie played a house show during the pandemic. That was our house. We felt bad for the bands that had nowhere to perform and we already had a studio in our basement, so we decided to add cameras and a switcher to stream the bands so they could make a few bucks. (We hosted over 600 shows at our pub in the 3 years it was open and nearly 80 shows from our home during the pandemic).

It was definitely nice seeing your name again and I have fond memories of some of our chats back in the day.

Hope all is well,

Brent Malnack