That Time Milli Vanilli's Tape Broke

A new film sends me back to my own personal would-be Watergate

The 50th anniversary of Richard Nixon’s resignation today takes me back to how influential the whole Watergate case had been to my own career path into journalism, inspired by young journalists who dug into the story, exposed wrongdoing and coverup that led to the takedown of the most powerful man.

I achieved nothing so historic or world-changing of course. Writing largely in entertainment and the arts affords few such opportunities.

However, there was the time that Milli Vanilli’s tape broke during a July 1989 concert I was reviewing at a local amusement park and I called them out on it. It may have been one of a number of incidents that spelled the group’s demise — capped by their producer claiming they didn’t sing a note on their 10 million selling album and the rescinding of their Best New Artist Grammy.

But at the time, 16 months before their German producer Frank Farian’s press conference — it certainly got no notice beyond The Hartford Courant circulation area and readers of overnight reviews.

So it’s a little surprising that a new biopic on the group, also out today, Girl You Know It’s True: The Milli Vanilli Story blows up the moment considerably as a potentially career-killing front page scoop.

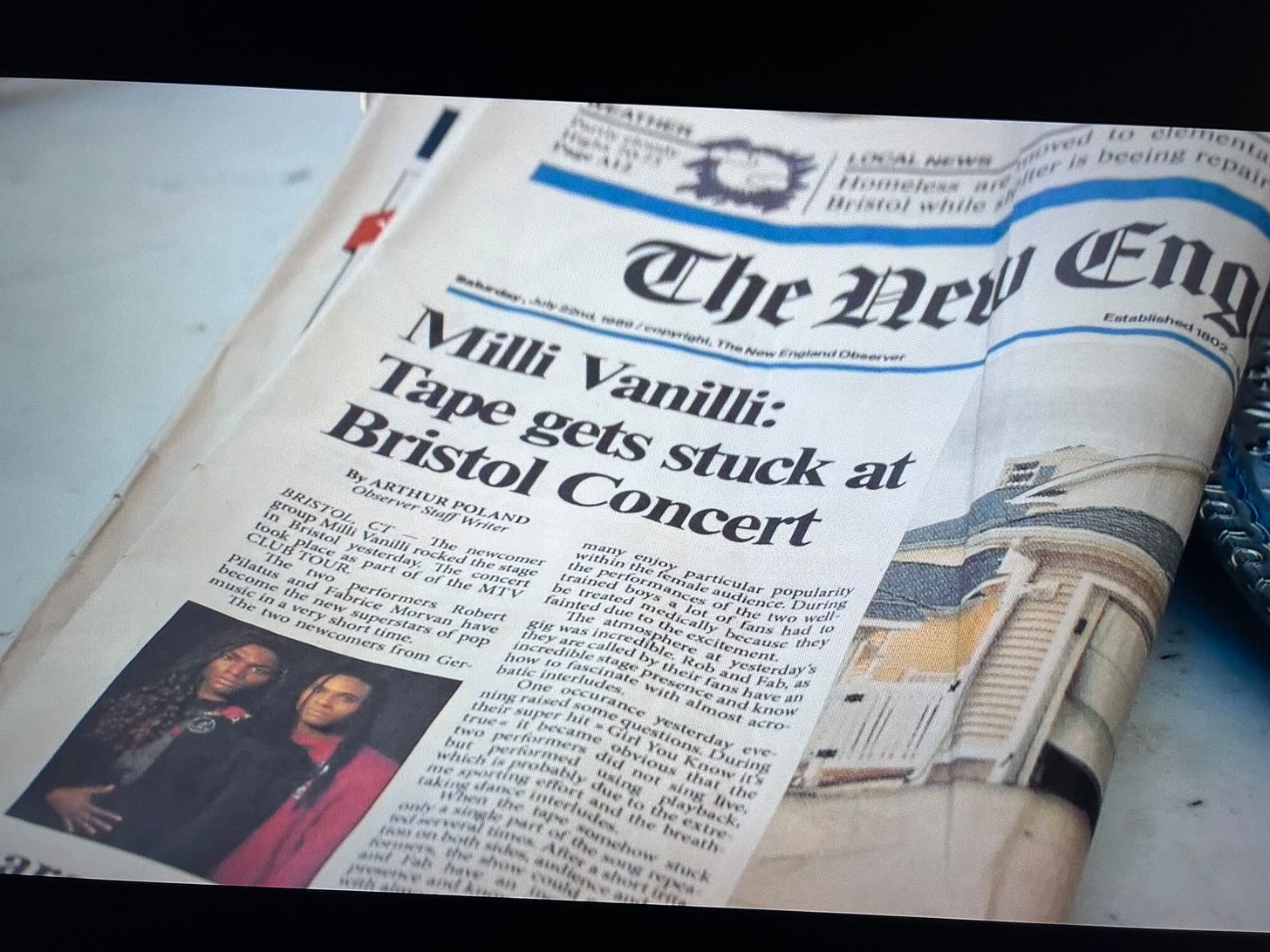

To think that any concert review for The Courant would appear above the fold on the front page is amusing enough, but the one in the film, for a strangely similarly designed newspaper called The New England Observer also gets the huge, accusatory headline, “Milli Vanilli: Tape Gets Stuck at Bristol Concert.”

In reality, the review was buried way back in Section C, page 8, and mention of the duo’s performance only came in the 11th paragraph, after discussing the sets of Tone Loc and Paula Abdul’s at the inaugural Club MTV Tour that also featured Was (Not Was) and the Information Society.

It described Milli Vanili as “a couple of guys from Europe who wear hot pants, grow their hair in long brands and are named Rob and Fab.

“Their big thing is to give each other flying high fives, or if they are really in a good mood, a flying crash into each other’s bare chests,” I wrote, concluding “This isn’t entertainment, it’s bad basketball.”

The tape breaking that was never front-page, career-killing news — and this is kind of a surprise to me now — was kind of buried in the one paragraph dealing with their music of Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan and their band.

“Their two hits are pleasant enough, forgettable stuff, but they sound too much alike. And everything else they do is much worse. Most telling is when they couldn’t get their synthesizer started for the beginning of their set, they hadn’t the faintest notion how to keep the audience entertained, so they cursed their instrument and stormed off stage.”

Certainly, it was an odd moment: Sudden silence in the big outdoor concert, the two frontmen looking at each other in horror and dashing off stage followed by a long, unexplained pause before, just as abruptly, the music came back on full bore with vocals before the two could come back on stage to reclaim their apparently dead microphones and continue the illusion.

It didn’t cause much fuss among the young audience, still looking forward to the headliners to come. And my comments certainly didn’t set the music world afire (though I’d bring it up more forcefully every time I wrote about their subsequent area appearances in the next year and the rise of lip synching among dance pop acts in general).

In the new movie, a manager utterly dismisses the Bristol glitch: “There’s stuff in the local paper, nothing in the major papers. Don’t worry about it.”

True enough. But in the same scene, any fretting is eclipsed by the sudden news that they’ve nabbed Grammy nominations for Best New Artist (though those nominees weren’t actually announced until five months later). Well a lot of things may shift in time and memory.

Because it was an MTV-sponsored tour, hosted by “Downtown” Julie Brown, some conjured up the idea that the incident was actually broadcast by them as well, though it never was.

A tape of the gaffe existed, but was never widely seen, and certainly didn’t go viral, until a 1997 VH1 Behind the Music on Milli Vanilli, where Morvan was coming clean. “I wanted to die,” he said then of the incident (of course he also said there were 80,000 watching — an exaggeration by a factor of about 10).

Later, the sound technician for the park concert series told me that their Emulator — an early synthesizer powered by 5-inch floppy discs — had crashed. “What was on their Emulator, I’m not sure,” he said, “but it caused them to go off stage, so it must have been pretty important.”

Pretty much unnoticed at the time, the glitch retained its place in history as time went on — and when Milli Vanilli were unmasked as vocal phonies and had to rescind their Grammys.

“I looked backstage and I heard what was going on and I couldn’t believe it,” Abdul told me in 1991 of the Milli Vanilli mishap, though later the tour manager has since said every act on the tour but Was (Not) Was relied on tapes.

At any rate, the new film Girl You Know It’s True, written and directed by Simon Verhoeven, takes its subject quite seriously and is a pretty good portrait of a time when looks mattered more than musicianship in the MTV era.

Tijan Njie and Elan Ben Ali are dead ringers for Rob and Fab, breakdancers from Germany and France who meet on a video set and decide to team up, only to be swooped up by manic German hitmaker Frank Farian (Matthias Schweighöfer) as literal frontman to the R&B he was concocting with other, less photogenic musicians and singers in the studio.

It includes a lot of details of the odd story, including the origin of the title track, the first Milli Vanilli hit, cribbed from a struggling musician in Maryland. In some sort of poetic justice, that guy is now listed as one of the film’s producer, as is Rob’s sister, Farian and Morvan himself.

Therefore, it generally gives a positive spin to the concert-fillers thought to be con-men — victims of the music madness around them (even though they succumb to the usual pop star excesses of girls and drugs).

The Connecticut concert, about 80 minutes into the film, is mislabeled as being from a “Lake Compounce Festival” in Bristol (no state given).

And while Lake Compounce — the oldest continuously operated amusement park in the U.S., across from the sprawling ESPN campus in central Connecticut — was for a time called Lake Compounce Festival Park when it ran a big concert series, its capacity was certainly not as large as depicted (or remembered by Morvan).

Still, now if you visit the amusement park, there’s now a plaque there, right by the Zoomerang, announcing the historic moment of their being caught.

But not, alas, by whom.